Why Organize

“Democracy is not something you believe in or a place to hang your hat, but it's something you do. You participate. If you stop doing it, democracy crumbles.”- Abbie Hoffman

Desegregation of schools, women’s right to vote, a five-day workweek-- these are things we may take for granted now. But these are hard-fought victories by organizers and activists, or rather people just like you. Political organizing is simply pooling our power as individual people in our representative democracy to make a change in our communities and society at large. Political and community organizing can be used to for everything from getting a speed bump on a busy street, to winning elections, and even fighting for larger policy issues in the country. For example, the civil rights struggle in America was a series of campaigns and actions.

*The term “actions” is used to describe events and tactics as part of a campaign.

It has been said in political processes and community campaigns that there are two main spheres of power. They are money and people. These are the two methods of influencing our representative political system. In our efforts, it’s is unlikely we will match the capital of the lobbies of a large corporation or industrial sector, so we must gather power through recruiting, training, and mobilizing activists to affect the positive change we seek to make. When it’s real and strong, history has shown people power can beat money.

A quick note: we do not claim to be the original creators of this methodology or ideas. We are merely passing them on as they were taught to us-- “each one teach one.”

ACTIVISM- activism is accepting confrontation. This is not meant purely in a physical sense, though at times in history, it has been. Activism is speaking up when you know wrong is being committed. Activism can feel awkward. It can feel scary. Activism can put you face to face with opposition you do not encounter in your everyday life. Your activism can see you vilified by some and this can be scary. As Saul Alinsky said, “Only in the frictionless vacuum of a nonexistent abstract world can movement or change occur without that abrasive friction of conflict.” Civilizations have risen and fallen at the feet of people like us. Remember, “This is what democracy looks like.”

Creating Goals

“Our goals can only be reached through a vehicle of a plan, in which we must fervently believe, and upon which we must vigorously act. There is no other route to success.” —Pablo Picasso

When creating your goal, it is important to know the difference between a goal, a strategy, and a tactic. In haste, untrained activists can react and create a goal that is just a tactic, or a piece of the puzzle. It is a common folly that must be avoided. For instance, say your group of activists is mad about a new racially biased policy passed by the Secretary of Education, so you plan a walkout at your school. Or, say your city is considering building a garbage incinerator on your street, and your group knows this will make the air in your neighborhood toxic. You and your group go protest in front of City Hall with a bull horn. I hope that you will see why accomplishing these actions alone is not likely to accomplish your overall goal. In both cases, these are singular actions that may have a chance of making the news, or influencing policy, but these are tactics that should be utilized in a larger campaign. Actions alone are not complete campaigns. To illustrate the difference between a goal, a strategy, and a tactic, consider a boxing match. A boxer's goal may be to beat the current champion. The strategy would be the overall fight plan-- to tire out the champion, and win the late rounds. The tactics would be the actual moves the fighter will use to achieve the strategy-- throw left hooks under the rib cage, jabs to the stomach, and lean on the champion when they grab the challenger.

In a campaign, a goal could be to stop the construction of a garbage incinerator from being built in your neighborhood. The strategy could be to get four City Council members to vote no on the incinerator. Tactics used could include the protest at City Hall with a bull horn, petitioning, bird-dogging, and rallies and media events (more on these tactics later).

Your goal will be the overall thing you want to accomplish. It could be a big overall long-term victory, like the passage of the U.S. Example Act. Or a short-term goal like getting your Senator to cosign or vote for The U.S. Example Act. This will depend on what role your group is planning to play.

In creating your goal, it is important to research the topic of your campaign. You need to know everything. You want to learn about your campaign’s decision-maker or decision-making body and find out about the people and groups that will make this possible. You want to know what a victory would look like in whatever deliberative body holds authority. What will it take to attain your victory? You may want to divide research among your group. For example, one-person research demographics in the area, one person research the decision-maker, one person research media stations in the area, etc. Situations and policies can change continuously, so research will make sure you are not caught off guard. Maybe your target resigns, or a new obstacle arises like a new opposition group is formed and influences one of your pillars of support. To be victorious, you must be fluid and adaptable. As Bruce Lee said, you must “be like water.”

S.M.A.R.T Goals

Goals need to be “SMART.”

Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic, and Time lined.

Specific- Making your goal specific means making it focused. It should be clear when you have achieved your goal.

Non-Specific: Do something about prison reform.

Specific: Pass a bill.

Measurable- Quantify your goals, large or small.

Non-Measurable: Spread awareness about elder abuse in nursing homes.

-If your group seeks to do something like spread awareness you can do that, but make it S.M.A.R.T.. You need to quantify it. For instance, five printed stories, two TV stories, etc. This way you have direction and focus, and you know when you are done.

Measurable: Get 2,000 petitions signed.

Actionable- Is this something we can act on?

Your group may not be able to get someone elected to Parliament in England. Maybe it is illegal for U.S. interests to involve themselves in English elections. So, for your group here in America, it is not actionable. Your group may be able to influence a U.S. Congressional election, or a school board election. But then again, maybe your group here in the U.S. can figure out how to influence a parliamentary election in the U.K..

Realistic- You can take this one with a grain of salt. It is important to dream big, however, if there are three people in your group and there is only one week to campaign, it is not realistic to say, create a goal of having your friend become the Presidential nominee. That said, shoot for the stars. Just because something has never been done before does not mean you will not be the first to do it. In organizing, we go about taking on seemingly unwinnable battles. Stay grounded, but be true to yourself. Reality is what you make it.

Time-limited/time lined- Recognize how long you can commit to accomplish your goal, and be realistic about how long it will take. If your group will only be together for a semester, then your campaign has to be done in that time. Create a timeline for your campaign.

Examples of non-S.M.A.R.T goals: Stop Pollution

Examples of S.M.A.R.T Goals: Block the building of a new trash incinerator in Pomona by getting the incinerator construction on the Nov 2nd ballot.

Picking a Target

Talent hits a target no one else can hit. Genius hits a target no one else can see.

DEFINE WHAT VICTORY LOOKS LIKE! In my opinion, this is the most important thing to know and will guide your campaign. Once you have a goal, you need to identify the governing body, the policymaker or decision-maker/s, or process that can make our goal possible. Is it voters? The Chair of the example committee? Who holds the power and what do they need to do to make your goal reality? Is it a measure, bill, amendment, proposal or a proclamation?

Again, research is key and needs to be continuous. After researching the topic of your campaign, you will be able to figure out who or what body can make your goal possible.

It is important that everyone involved in your campaign can easily identify what victory will look like. Ex: We will stop the building of the incinerator when 6 of 10 city council members vote no example measure 12.

-Knowing this information will help create smaller goals for your campaign. For example, maybe 500,000 voters need to sign a petition to bring example measure 12 to the council.

It is a good idea to reach out to the decision-maker/target before you begin your campaign. It may be the case that your group accomplishes your goal with a simple meeting (though not likely still be prepared to win have props for the photo op etc). Be courteous and professional. State your ask. If s/he says yes or no, follow up. If yes, hold them accountable publicly. If no, then begin your campaign. If they will not meet with you or your group, it might still be a good idea to introduce yourself and inform the target of your campaign.

*You and your group should decide the tone and messaging of your campaign. More about messaging later, but this should be based on your research. If the only people who have power to influence your decision-maker are the Elderly Temperance League, then it’s probably not a good idea to have you or your organization/group be perceived as belligerent. That said, stay aware of how you want to be seen. During the Civil Rights movement, the activists that participated in sit-ins from the student nonviolent coordinating committee wore suits. They wanted to present themselves as professional and dignified, however, the Black Panthers wanted to be perceived as a paramilitary organization. If your group is angry, you can be angry. Just be strategic. Passive resistance fits some situations, but maybe not others. You decide but this is something that should be understood by your group’s activists in the campaign planning stages. Your messaging may change as the campaign continues or may be different at different actions.

Power Mapping

Now that we know who or what our target is (the decision-maker), and we have a firm understanding of the decision-making process, we can Power Map. Power Mapping is a brainstorming tool that will help you create a strategy to influence your campaigns decision maker or makers. This can be done in various ways. This is one way, but find what works for you. Do this with the group; put your heads together. Participating in the planning will also increase the individual investment your group’s activists have in the campaign.

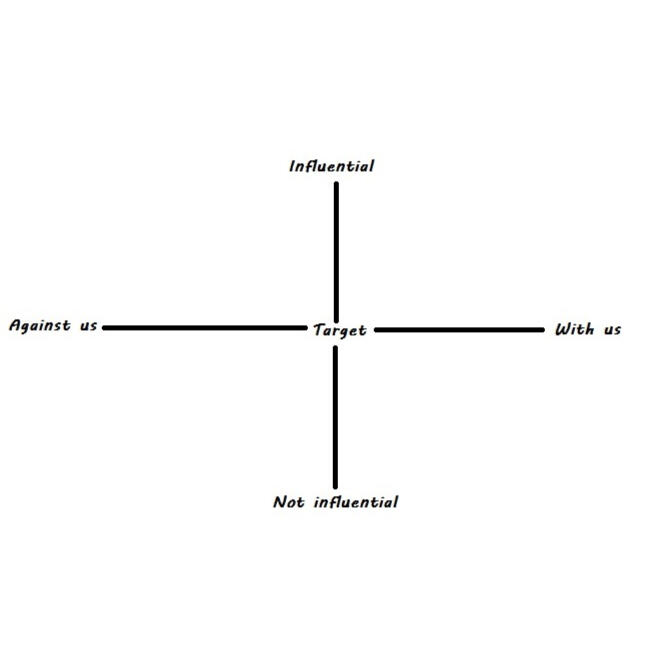

To start, you probably want to use a whiteboard or a big sheet of paper. In the center put the name of the target. Then make a horizontal line with your target in the center. On one side write “with” on the other side write “against.” Then do the same with a vertical line, again with the target in the center on one side write “influential” and on the opposite side write “not influential.” It should look something like this:

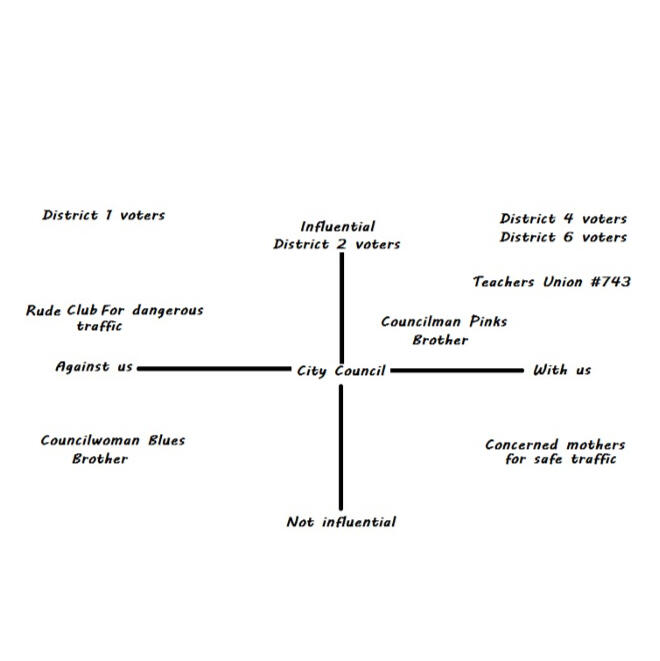

Then, fill it out having members of your group add input (at this point the members of your group should have a better idea of groups and influence based on their research). The more influence a group or organization has on the decision-maker put it in the proper position. Then, whether they are with or against you, decides where the group or organization goes left or right. Ask the questions, who is with us? Who is against our goal? Who has influence? Who may support us? When your group is done it should look something like the picture below (I'm doing this one with my goal as getting a stop sign on imaginary 7th street with imaginary groups and considerations):

Now we can see who is with us who is against us, who we have influence over, and who has influence of our decision-maker. From this example, we could get an idea of what the campaign will look like. District 6 and 4 voters are with us. We may plan to recruit our base from there. Teachers union #743 is with us, and influential. We could approach them for support. District 2 voters are influential and can likely still be swayed to our side. (I would recommend designating a note-taker or secretary to photograph and keep your power map.) These are all things to keep in mind as we move into our next step.

Creating Strategies and Tactics

“Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without Strategy is the noise before defeat” - Sun Tzu

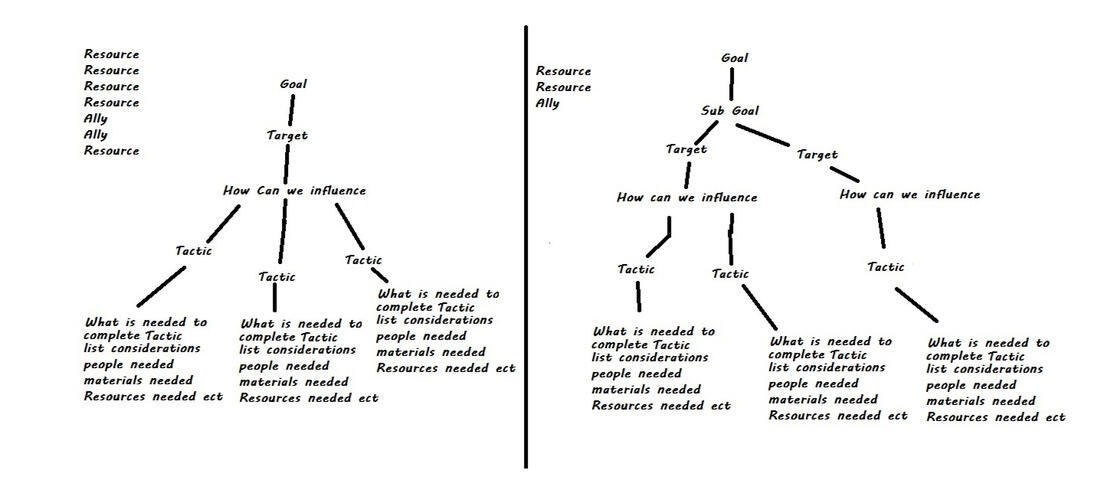

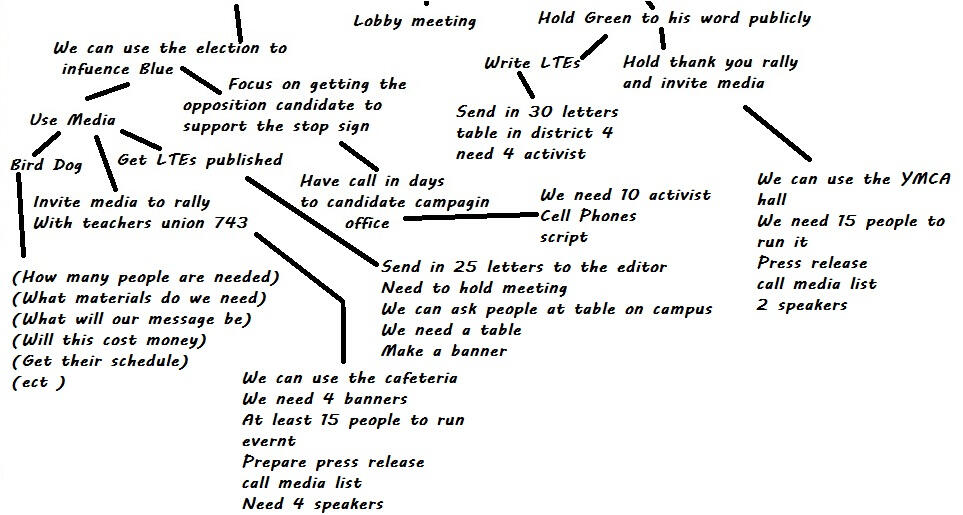

This is another step you want to complete with your group on a whiteboard or large paper. This will be used to help you identify and plan your strategy and tactics. I use a flow chart. Start on the right side of the paper. Write a column listing all the resources and allies your group has starting out (these are things you want fresh in your mind as you go through your brainstorming). Then, you start with your overall goal in the top right, move down to your sub-goals and targets. Figure out how you can influence your targets, then tactics that can accomplish that. Create new columns as needed. With each, you want to think of what you will need to consider and factor that into your planning. The members of your group should have some ideas from power mapping and doing their research.

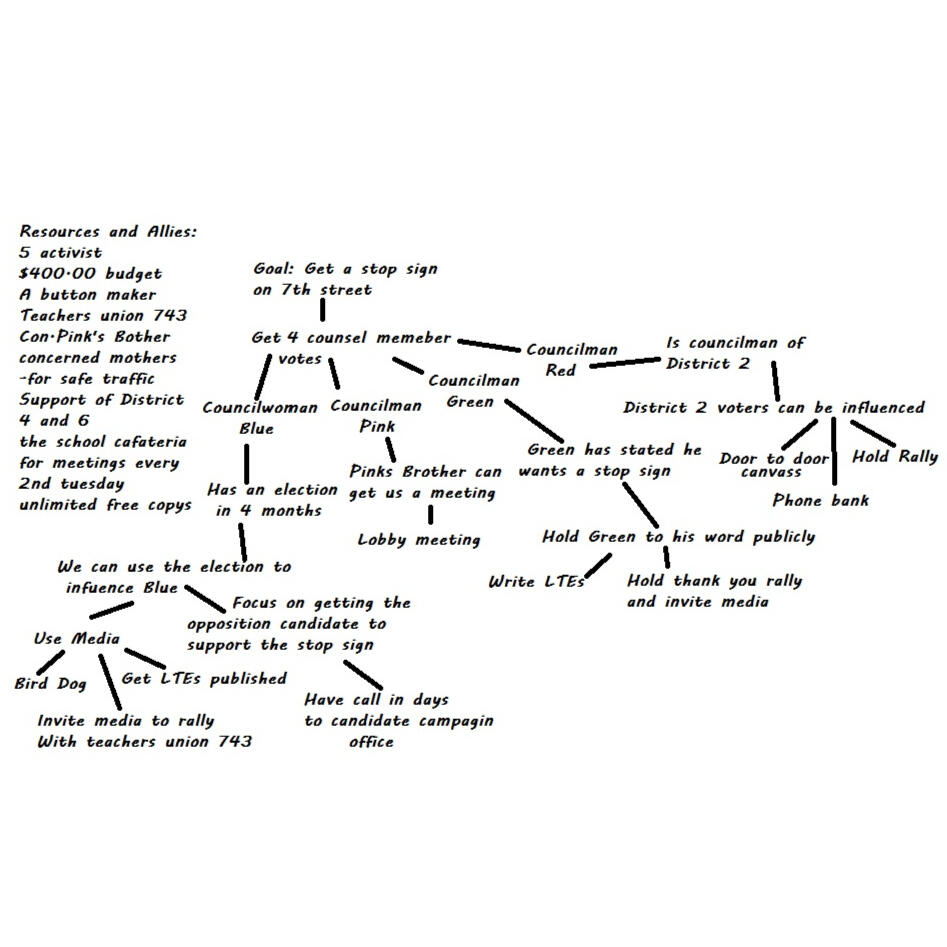

I'll demonstrate here using the same fictional goal of getting a stop sign on 7th Street. In this picture, I'll stop when we have identified our tactics:

As you see, we have used strategy factoring until we ended up with tactics for the campaign. Our overall goal is to get a stop sign on 7th Street. Through our research, we have learned that we only need four City Council votes for the stop sign. We have identified the four Council people whose support we believe we can win. Going further, we have created four strategies to win individual Council members support. Lastly, we have identified the tactics we will use to accomplish each strategy. At this point you should make sure your group is all on the same page and in agreement on the strategies and tactics you will use. So, from our strategy factoring, we see that in order to win Councilman Reds support, our strategy will be to influence District Two voters. The tactics we will use will be door to door canvassing, phone banks and holding rallies until Councilman Red has agreed to support the stop sign.

Councilman Green stated her support for the stop sign so our strategy with her will be to hold him to it.

The next step in your factoring is to consider what you will need to hold your events/complete your tactics. How many people do we need? What materials will we need? Will this cost money? Do we need a permit? Example below:

In the research, picking a target, power mapping, and strategy factoring, you should get a better idea of what the goals of your campaign need to be. You may even realize you need to change a goal or even a sub-target. This is okay. Remember, “Campaign plans are written in pencil,” and again “be like water.”

Creating a timeline

“A goal without a timeline is just a dream.”

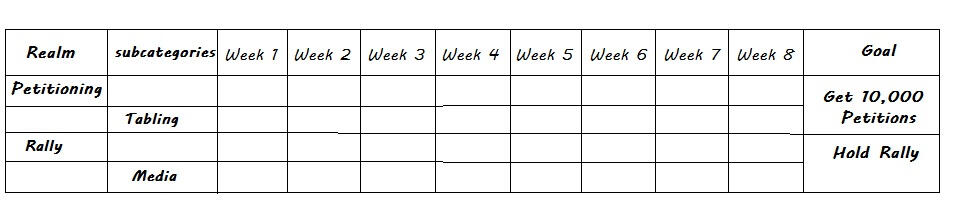

One of the most important steps in your campaign plan will be creating a timeline. This is also important to do with your group. Maybe half of your members have a final late into your campaign when you would have planned an event. Again, this is something I would do on a whiteboard or a big sheet of paper. Now that we have our goals, we have some sub-goals and we have planned some events. Work backwards from your goals and plan your timeline to have escalating tactics. For instance, if you have petitioned and gotten an issue on a ballot, as the election gets closer you want the energy to build heading into the election. If it is an issue or social justice-based campaign, you want your opposition to feel that your campaign will continue to grow and get bigger. Structuring your campaigning for escalation can also be beneficial for the growth of individual activist in your group. After coming to a first meeting, it is unlikely that a new activist will be ready or have the confidence for the final conflict of your campaign. This escalating structure will help build the confidence of your activists and solidify messaging as well.

As you create your timeline, working backwards from your goals will help create benchmarks or sub-goals. Say the goal of our group is to get 10,000 petitions, and we have 20 weeks left in the school year or before the election. Then, by working backwards from the goal we know that in ten weeks we need to have 5,000 petitions. Placing smaller numerical goals on your timeline will give you benchmarks or sub-goals to reach. This will allow you to see if you are on track. This will allow you to reevaluate and alter your plan - “be like water”. This goal of 10,000 petitions in 20 weeks means that to stay on track we would need 500 petitions a week. To make the math easy, say I have four people in my group, and they were able to get 400 petitions in the first week. You can then assume one of your activists can get 100 petitions a week. So now you know you must make a goal of getting at least one more activist in your group. If it was strenuous and you know getting those 100 petitions was tough on your members, then you can decide you need ten total activists to each get 50 petitions each a week. Revisiting your goals and progress on a timeline will help keep you on track. This is also a good example of why you need to constantly be recruiting, but more on that later. This is a simple example just for visual effect:

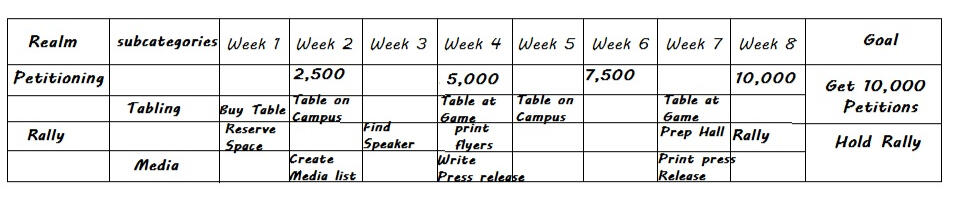

As you can see in this example, we have our main goals on the right. Then we have our “realms” which are the main categories of our campaign. Then we have our subcategories or considerations related to the realm of the campaign. This will help make sure important considerations are not neglected. When you are done it should look something like this (most likely with a lot more subcategories):

In this example, we can see that week four has multiple tasks to complete, while week six has nothing planned. This is why you create the timeline. We can move some a for week 4 to week 6 or week 3. The goal is to not overwork you or your group. Breaking tasks up on our timeline can make a large overwhelming task manageable.

Things will change, and you'll have to make changes to your timeline. This is okay. Make sure all members are updated when things have to be changed, “like water.”